Before scientists do anything there is often a ready made public perception of how good or how bad it is going to be, derived from this social, literary and cultural precognition. Popular culture talks about space-rockets before there are space-rockets, test-tube babies before there are test-tube babies and clones before there are clones.

Rather, they are a critical part of the process of developing science and technology they can inspire or, indeed, discourage researchers to turn what is thinkable into new technologies and they can frame the ways in which the ‘public’ reacts to scientific innovations. The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that popular culture and imagination do not simply follow and reflect science. This paper examines the visual and verbal imagery surrounding the various ‘submarines’ that have travelled through popular imagination from Verne’s Nautilus, driven by Captain Nemo, up to the more recent representations of nano-submersibles, some of them fact, some of them fiction and many more floating between the two.It retraces the voyages of iconic submarines from the 1870s, when Verne wrote Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, up to the present, from the journey through the hidden space of the world’s oceans on board the hidden space of a luxurious submarine, to expeditions into the hidden space of the human body and beyond to outer space. They continuously serve to sciencefictionalise science fact and blur the boundaries between cultural visions and scientific reality. Vehicular utopias, from Jules Verne’s Nautilus voyaging under the sea to nanomachines navigating through our bloodstreams, have, for a long time, filled this surreal gap between the technologically possible and the technologically real and can have an immediate and long lasting hold on public imagination. This is due to NST’s radical future orientation, which opens up a gap between what is technoscientifically possible today and its inflated promises for the future.”. He comes to the conclusion that “the relation between SF narrative elements and NST is not external but internal. This view was echoed by López in his 2004 article “Bridging the Gaps: Science fiction in nanotechnology”, in which he explores how nanoscientists themselves have employed devices from sci-fi literature to argue the case for nanoscience. However, there is, as Richard Jones pointed out in a recent article on “The Future of Nanotechnology”, an almost a surreal gap between what the technology is believed to promise (or threatens to create) and what it actually delivers – a gap that certain science fiction scenarios can easily fill, be they of the dystopian, grey goo type, or the utopian, spectacular voyage, type. Another popular image of nanotechnology, the view that it will lead to tiny robotic submarines travelling through the human bloodstream and repairing or healing our bodies is equally ubiquitous. This so-called ‘grey goo’ scenario was first described by Drexler in his book Engines of Creation, a scenario he now thinks unlikely (as of 11 June, 2004), but which has been integrated into fictional narratives such as Michael Crichton’s novel Prey, has provoked comments by the Prince of Wales, lead to inquiries by the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering in the UK, and, in general, taps into wide-spread fears about loss of control over technologies. Some, however, have claimed that nanotechnology might lead to nanoassemblers and potentially self-replicating nanomachines swamping life on earth.

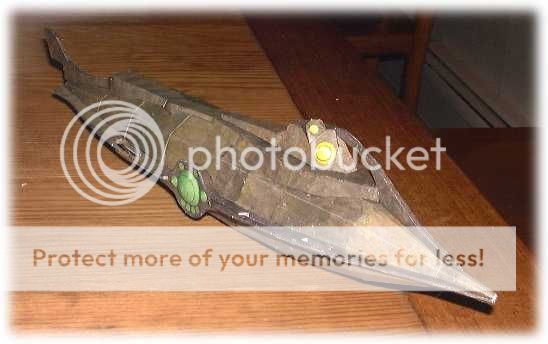

Submarine cartoon nautilus windows#

The potential applications are exceptionally diverse and beneficial, ranging from self-cleaning windows and clothes to ropes to tether satellites to the earth’s surface, to new medicines”. Its aim is to advance science at atomic and molecular level in order to make materials and devices with novel and enhanced properties.

“Nanotechnology is a rapidly advancing and truly multidisciplinary field involving subjects such as physics, chemistry, engineering, electronics and biology.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)